When it comes to satisfying consumer demand, brand owners are so often left trying to find the right balance in compromise. This is certainly true in packaging design, where sustainability and affordability are often at odds. “Many buying decisions are based upon a combination of choices rather than a binary either/or type scenario,” says Ray Wodar, global director of business consulting for consumer packaged goods and retail at Dassault Systèmes. He points to statistics showing that although 84% of consumers say sustainability is an important consideration, 50% say they’re not sure they would pay a premium for sustainable products during times of inflation. “It’s clear that companies must strike a balance between sustainability and price.”

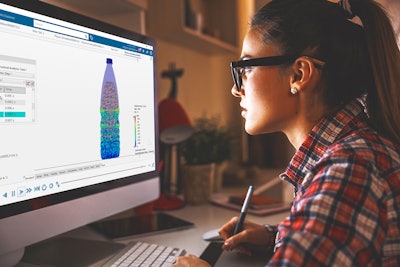

And those are just two of the package design considerations that must be taken into account in today’s environment, Wodar says, detailing considerations in materials selection, lightweight design, reusability/recycling, materials lifecycle, dyes and coatings, and others. Speaking on an Innovation Stage at PACK EXPO Las Vegas, Wodar was advocating for the “infinite possibilities” of designing with virtual twins—a system from Dassault Systèmes that uses virtual data to simulate real-world multi-physics in silico.

| Ray Wodar's Innovation Stage presentation, "Infinite Possibilities With Virtual Twin Packaging Value Chain," is available on demand through PACK EXPO Xpress. |

Cheaper, more robust compute power has democratized simulation, Wodar says. “By using virtual design models that mimic real-world physics, we have the ability to optimize our designs for multiple factors,” he says, noting the time saved through virtual models as well as the cost of physical designs and prototypes.

Digitalization reduces complexity

The use of digital twins has more commonly been associated with more high-tech manufacturing environments, but package design is also beginning to realize the benefits. “We have seen the core advanced industries—automotive, aerospace, high-tech—really embrace the capabilities of the digital twin, or what we call the virtual twin. And I would say their maturity levels are a little bit more advanced compared to the consumer packaged goods industry as a whole. But I think that gap is tightening,” Wodar says. “A few years ago, you’d have industry leaders like P&G or Unilever, some of the big OEMs, investing there. But now you’re seeing it become a predominant digital infrastructure strategy these days and providing capabilities…certainly around modeling and simulation.”

More investment is going into virtual twins for CPG packaging, according to Wodar. “People are seeing direct benefits of compressing things like time to market, reducing their internal costs from a labor perspective,” he says.

There’s also a transformation happening around business strategy—in the past using agencies to do a lot of the package engineering with that becoming part of the core business inside the CPG. “They see that as a competitive advantage now to have the innovative technology as IP that they own,” Wodar says.

To design the right package, Wodar emphasizes the need to move from linear to circular models, showing a well-known butterfly diagram from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation to demonstrate the continuous flow of materials in a circular economy—with the biological cycle on the left and technical cycle on the right. Companies have traditionally put a lot of money into the right side of the model, which is focused on reuse and recycling, but recently, more investment has gone into innovation around the left side, including compostable materials, he says.

The point is that there is a high level of complexity when considering packaging design, and it needs to be managed in a holistic way, Wodar says. “We need to compute a tradeoff analysis against four main pillars in all aspects of design and manufacturing of a new or existing product,” he says. “Virtualizing the four pillars—environment, business, performance, and quality—allows you to trial infinite possibilities. You can run tradeoff analysis against thousands of virtual trials.”

Instead of the dozens of physical prototypes you might trial without virtualization, you might actually prototype substantially fewer candidates, Wodar adds. “But those candidates can be run more efficiently, closer to the end requirements and goals, making the time more compressed, and allowing more capital to be spent on a more focused and sharpened outcome.”

Designing for environmental impact

Wodar details a full range of factors that can be tested against in a virtual eco design. “Eco designing allows the designer to look at the solution with a holistic mindset—the ecosystem mindset rather than the singular product mindset,” he says.

Material selection is critical not only in the package performance but also its impact on the environment. Virtual eco design makes it possible to calculate a precise eco footprint. “And remember, 80% of the environmental impact is determined early in the design process,” Wodar emphasizes. “It is crucial that these factors are considered as early as possible in the process.”

The virtual packaging value chain includes several steps from the beginning of the raw material selection through to the consumer:

- Raw material suppliers

- Packaging suppliers

- Design agency

- Brand manufacturers

- Warehouse distribution

- Delivery

- Home and consumer

- Materials recovery facilities

“Today, most of these are optimized in silos—a non-connected chain of events,” Wodar says. “We believe interconnecting some if not all of these processes can produce a lot of significant benefits.”

In a virtually enabled world—with virtual data mimicking real-world packaging—each part of the value chain can be optimized while also understanding the impact on the other parts of the value chain. This not only optimizes the process, but saves considerable costs and resources, according to Wodar, who notes a 30 to 50% reduction in packaging material costs and a 75% reduction of development time, among other savings. He provides examples of cost, material, and productivity benefits savings at Unilever, PepsiCo, and others through the use of virtual twins.

Wodar emphasizes the importance of getting all parties involved in creating sustainable packaging. “It’s a massive challenge, and it doesn’t just sit in one part of the value chain’s responsibility. It’s the OEM, it’s government, it’s local municipalities,” he says. “It’s really a holistic problem because if you just solve one part of the puzzle, at the end of the day, you’re not going to reach the goal of the packaging being sustainable, and it won’t drive the circular economic model at all.”