The tallest, 10- and 12-count multipacks, take advantage of an overhead squaring lug feature on the cartoner, which is helpful due to the cartons’ heights.

The tallest, 10- and 12-count multipacks, take advantage of an overhead squaring lug feature on the cartoner, which is helpful due to the cartons’ heights.

Predictably, packaging came under scrutiny during this brand revolution. At that point, multipacks for just about every brand and variety of canned seafood had long used robust, printed shrink bundling film, capable of tightly containing heavy cans of seafood in the formats we still see on retail shelves, like a 4x2 8-pack of 5-oz cans. Bumble Bee was no exception in using this pack style, since shrink bundling was (and continues to be) a capable method of multipack delivery that withstands the supply chain well. Bumble Bee’s most common formats were 4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, and 12-pack cans, either 5- or 7-oz, interchangeably called shrink bundles or cluster packs.

Specific to the Bumble Bee facility in Santa Fe Springs, Calif., shrink film was applied to build shrink bundle packs by a 25-year-old shrink overwrap machine that was on its last legs. The company couldn’t secure good support for such an old model, and it was frequently causing downtime on the line.

That was an internal, operational drawback to the shrink-bundling situation at Bumble Bee, but it was one that could be easily solved with investment in a new shrink bundler. A more enterprise-altering, consumer-facing drawback? The films aren’t readily recyclable.

This second drawback was key since consumer perceptions around plastics were changing. Especially early in the sustainability revolution, this stemmed from perceptions around the threat of ocean plastics, and later evolved into a broader consumer desire for recyclability and circularity.

“We started looking at paperboard a couple of years ago as part of our Seafood Future Commitment,” former Bumble Bee CEO Jan Tharp told me at PACK EXPO Las Vegas last year. “In it, we talk about our purpose of feeding people’s lives through the power of the ocean, and that means we have to protect and nurture the ocean. Because that’s one of our pillars, we want to make sure that when we are looking at our packaging, we want to be sure that the packages we’re producing are readily recyclable. For the most part, they are; 96% of our packaging is readily recyclable. But we want to keep that number moving forward to hit 100%.

“That brought us forward to this package, and our partnership with R.A Jones,” she continued. “When we decided to go to a paperboard carton, we realized it’s so much more than just a carton. When you look at the beneficiaries of this project, it’s the consumers first. Aesthetically, a shrink bundle isn’t very pleasing, and it’s difficult for a consumer to open. Also, our direct customers [retailers] will benefit. Nine out of 12 of our top customers have made commitments to getting into readily recyclable packaging, packages that are compostable, or packages that have increased their ability to be recycled instead of going to landfill. From a customer perspective, this new pack meets their needs.”

Former Bumble Bee SVP, Global Corporate Responsibility, Leslie Hushka added that multipack cartons can be displayed horizontally or vertically in a retail setting, mentioning that all the major retailers want to be able to display packages vertically to optimize shelf space.

“And we’re a beneficiary as well. Since [the paperboard carton] is readily recyclable, it meets our commitment to protect the ocean,” Tharp said. “And by protecting the ocean, we’re protecting people. Between us, our retail customers, and the end consumer, it’s a win-win-win.”

The paperboard isn’t just recyclable, it also incorporates post-consumer recycled content to begin with, introducing circularity to the pack style.

“We’ll be working with the R.A Jones team over time to get that as close to 100% as possible, and still get all the nice aesthetic qualities we get out of the package now,” Hushka said at the PACK EXPO Las Vegas Booth last year.

Since then, Bumble Bee awarded the paperboard converting contract to Malnove of Utah to supply the one-side printed carton blanks that run on the new cartoner. The new pack format began appearing on shelves in late spring of 2022.

“R.A Jones was forward-thinking in having more flexibility in materials,” Tharp told me at PACK EXPO Las Vegas. “For instance, what if we wanted to down-gauge that material? What if there’s a paperboard material that comes out that we didn’t even know existed? A lot of what they did on this piece of equipment was take into consideration ultimate flexibility. And when you talk to CPGs, that’s our number one issue with OEMs—we spend a lot of capital on a piece of equipment, and then marketing wants to change something and we’ve got to buy another piece of equipment. I’m thrilled that there’s flexibility built into this machine, so we can grow with it.”

New equipment for a new direction

As mentioned previously, in 2019 Bumble Bee was probably nearly due for new equipment anyway. The older shrink bundling unit in Santa Fe Springs was causing downtime, so it was time to make a change. Facilities Engineering Manager Joe Carney was already investigating top-down shrink bundling, aiming at more of a sleever-style machine instead of an overwrapper, when paperboard first emerged as a possibility from corporate.

“We knew it was time to get a new unit. The upstream equipment wasn’t new per se, but the shrink bundler was definitely the bottleneck and it had to be replaced,” says Brett Butler, VP/GM. “But the decision to go to a recycled paperboard unit, that was a whole new venture for us here at the facility. But with legacy equipment nearing the end of its life, and both our own leadership and our customers pushing for more sustainable options—Costco, one of our primary customers, had recently made this commitment—we asked ourselves, ‘Is this a time to make a change here? Can we move away from plastic?’”

Given the unique intersection of circumstances and trends, Carney in late 2019 pivoted from his search for shrink sleeve OEMs to begin to seek out cartoner suppliers. He had a checklist of criteria to qualify for consideration. The primary driver was being able to run printed, recycled-content paperboard cartons that could be readily recyclable. Beyond that, Carney sought an OEM partner that could deliver equivalent line speed to the legacy equipment [pushing 300 multipacks/min for smaller formats] and deliver good changeover characteristics to be able to handle a lot of different SKUs and formats. In an unforeseeable wrinkle, this selection process overlapped the onset of the pandemic in 2020. This meant a late-emerging differentiator was finding a partner that could meet both service and operational needs when travel limitations and facility shutdowns were occurring.  Installation of the new cartoner at Bumble Bee.

Installation of the new cartoner at Bumble Bee.

“But I checked with all of the equipment vendors that I’d dealt with in the past, and none of them made carton machines,” Carney says. “Brett [Butler] and I discussed it, and he pointed me in the direction of PMMI. I used the PMMI website to get a list of carton machine manufacturers and got to an initial list of 14 vendors, and we went from there.”

| Speaking of vendor selection, read more about ProSource, a free online directory with 900 categories of validated suppliers of packaging machinery, materials, and service solutions. With a powerful search engine and the ability to filter solutions by machine feature and package type, ProSource brings vetted suppliers to you. Visit www.prosource.org today. |

Vendor selection factors

“Because we weren’t accustomed to cartoning, we had to find out if there were even machines available that could keep up with our speeds. How many machines would we need? We only had limited space in our facility,” Butler says.

Also, the legacy shrink bundling equipment was three-up, meaning its output was three separate bundles of a given format, each into a lane of its own. A bump/turner assembly oriented the bundles, and they lined up perfectly into three outfeed lanes.

“One of the bigger hurdles I anticipated was getting a new unit that would be able to turn and orient the new cartons uniformly from a single-lane machine into that three-lane conveyor at the outfeed,” Carney says. “Nobody made a dual or triple-lane out [feed].”

Inability to meet speed requirements vetted out quite a few of the original 14 potential vendors at the outset, and four early favorites quickly emerged. Of those four, only two were able to propose a single-machine solution to accommodate the speeds of nearly 285-300 cartons/minute speeds for 5-oz can 4-packs. The existing space constraints in the facility made a single machine the preferred route, leaving two qualified, final candidates. R.A Jones’ Meridian XR MPS-300 won out in the end as the cartoner of choice.

“One of the bigger reasons that Brett and I decided to go with R.A Jones was that they already had an in-market machine doing the same size can, stacked four high, for a pet food application,” Carney says of the final decision. “So they were already handling the stacked can.”

In Carney’s experience, stacked cans can prove problematic. Bumble Bee’s legacy shrink bundler, for instance, had issues with the stacks falling over prior to bundling, or sometimes even during bundling, thanks to nesting issues with the cans. The in-market pet food application proved to Carney that the R.A Jones equipment had solved for that problem.  Bumble Bee now produces 5- and 7-oz cans of tuna in paperboard multipacks from 4-count to 12-count.

Bumble Bee now produces 5- and 7-oz cans of tuna in paperboard multipacks from 4-count to 12-count.

“Another reason we liked R.A Jones was because, in the past, they had integrated a Nercon accelerator unit at the discharge of their machine with an Intralox turner/diverter unit that would take the single-unit cartons coming out, turn them lengthwise, and then divert them into the lanes evenly. We have the machine set now so that it diverts three into each row, and it alternates between the three rows as the line runs. [R.A Jones] had already proven they could integrate that equipment into the standard units, on the discharge on their machines. And they did the integration for our own machine with the Nercon and Intralox modules; when we were there for the FATs, everything was set up and functioning.”

The final factor in R.A Jones’ favor for Butler and Carney was the Acc-U-Change system that was available on the Meridian XR MPS-300.

Acc-U-Change and other custom features

Manufacturing in general is straining to replace a quickly retiring workforce, weather the post-pandemic “Great Resignation,” and find and retain capable equipment operators in a tight labor market. Bumble Bee is no exception, but don’t just take their word for it. Ken VonderHaar, Global Director, Can Division at Anheuser- Busch, tells us on in this Packaging World Take Five Video that his main requirement from OEM partners in machine design is simplicity and intuitiveness to accommodate a younger, less experienced workforce. For Bumble Bee, an additional level of complexity comes from frequent changeovers and format changes. Each case holds six multipack cartons. That’s true whether the carton is a 4-pack of cans or 12-pack of cans. All cases hold six cartons, and the case format is that of an overwrapped tray.  Printed paperboard cartons are opened from magazines of 2D blanks by way of mechanical gripers, plus an “elegant” air-assist carton opening feature to ensure the cartons fully open.

Printed paperboard cartons are opened from magazines of 2D blanks by way of mechanical gripers, plus an “elegant” air-assist carton opening feature to ensure the cartons fully open.

“But we change sizes on that machine four to six times a day, and we’ll run only a few thousand cases on our smaller runs. Our larger runs are only six or eight thousand cases. That means a lot of changeovers,” Carney says. “On the older shrink bundling machine, we had gone through the process of center-lining; putting marks on the machine where everything’s supposed to be set given each different size. With the Acc-U-Change system on the Meridian XR MPS-300 cartoner, the machine self-centerlines. Operators have to set it within specific tolerances, or the machine won’t run. It was an optional feature and a cost add-on, but it has been very beneficial.”

Within the Acc-U-Change system, every changepart carries RFID information. When each changepart is swapped out, the platform reads the RFID to find out whether or not it’s the correct changepart for the recipe indicated, and if it’s installed correctly. A red light/green light or “go/no-go” system indicates to operators if that change part is good to go. The system also features a mobile touchscreen tablet to assist the operator. The platform simply will not allow the machine to start back up until every change part is validated as a go. An operator likely wouldn’t be tempted to even try unless all the lights are green, validating that all the right parts are locked into the correct positions.

| Watch R.A Jones' CTO Jeff Wintring walk Packaging World through the Meridian XR MPS-300 cartoner at PACK EXPO Las Vegas last year, explaining features and capabilities as he goes. |

Strictly from a changeover perspective, the process on any R.A Jones machine remains largely the same whether it has the Acc-U-Change feature or not, just with the added measure of validated assuredness. The real gains come in the ensuing startup, which can be said to be a vertical startup. There’s no time wasted dialing the machine in, and potentially creating waste and scrap as an operator hones the machine into specific tolerances and slowly speeds it up to maximum capacity.

Even upper management was impressed by Acc-U-Change, given the current labor market. As then-CEO Tharp told me at PACK EXPO Las Vegas last year, “The labor component is an important element of this story. We’re struggling to get labor, both skilled and unskilled. But when you look at some of the design elements that went into this machine, they made it easy so that we can have machine operators who bullet-proof the machine. We don’t need a maintenance person with a Harvard MBA to do changeovers. Acc-U-Change is a huge benefit to us. Honestly, it’s color-coded, so I could probably do it; I could probably go in and do a changeover on the machine. That’s huge when you think about addressing the key issues affecting CPGs, and labor being chief among them.”

Another unique optional feature on this custom Meridian XR MPS-300 system is an overhead squaring lug to accommodate to the heights of the taller cartons. That was originally an option, but in the end, it became a necessity because the 10- and 12-pack cartons are so high, the overhead squaring lug is required to keep a carton straight while the cans are loaded. The existing carton lugs are about 6-in. tall, so 4-, 6-, and 8-pack cartons run without the need of the overhead. But the tallest cartons extend above 6 in., so they need the overhead assistance.  Infeed of 5-oz and 7-oz canned and glue-applied labeled product into the cartoner at the Santa Fe, Calif. Bumble Bee facility. Note the layout of three parallel tracks, with product first entering the space and feeding the cartoner on the center track. After product is cartoned and laned, it turns sharply 180 deg, carrying product downstream while parallel to the cartoner. Product then takes another, wider 180-deg turn around the cartoner, and finally travels parallel to the previous two tracks again for tray packing.

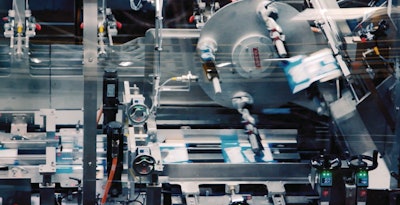

Infeed of 5-oz and 7-oz canned and glue-applied labeled product into the cartoner at the Santa Fe, Calif. Bumble Bee facility. Note the layout of three parallel tracks, with product first entering the space and feeding the cartoner on the center track. After product is cartoned and laned, it turns sharply 180 deg, carrying product downstream while parallel to the cartoner. Product then takes another, wider 180-deg turn around the cartoner, and finally travels parallel to the previous two tracks again for tray packing.

Bumble Bee also opted for an air-assist carton opener. The paperboard cartons are input into the system as flat folded blanks, mechanically picked out of a magazine, that need to be opened and loaded with stacked cans. There’s a mechanical arm that accomplishes that, but a pair of air knives help to pop the cartons open and limit the number of incomplete carton-opening cycles due to inconsistencies in the die-cut paperboard itself. At up to 300 cartons/minute, this is essential.

“It’s an elegant solution,” Patrick Costello, Director, Strategic Systems Engineering at Bumble Bee says of the air assist system. “It definitely moved the carton-opening bottleneck elsewhere.”

Tweaking the line to accommodate a ‘pointier’ format

Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good. Fitting the full cartoning system, including the standard Meridian frame and the downstream Nercon and the Intralox components, was close, but it all came together within 1⁄4 of an inch in a condensed space. Today, Butler laughs about how that worked out, with practically no room to spare. But the early engineering and planning between Carney and R.A Jones’ Tom Kinnett, with help from conveyor supplier Regal Rexnord Automation Solutions, proved spot on.

“It fit exactly in the space we had,” Carney says. “I had to remove the existing infeed and dynamic transfer, and I worked with Arrowhead to build and install a new dynamic transfer on the main feed conveyor. There previously was a ‘Y’ section with a diverter that used to take the cans off the main conveyor [for loose can runs, product not being multipacked], or it would divert the cans over to the shrink bundler [for multipacks]. It was about four or five feet farther forward up the line from the main conveyor, so it needed to be removed to get the infeed space we needed. R.A Jones had their set of CAD drawings, and Arrowhead had their own, but we combined the two, managed the offsets, and everything lined up. After trimming a little bit off the discharge after the turner/divider and laner, everything bolted together to within a quarter to a half an inch.”

Costello, an engineer who came in late to the project, long after the CAD plans were made, marvels at the fit.

“I’ve only been with Bumble Bee a little over a year, and it’s really astonishing the level of accuracy, and it’s a tribute to Joe [Carney] and Tom Kinnett at R.A Jones in leading that charge. The machine would fit, but all the dimensioning was through the conveyor systems. It was pretty amazing how well it worked out.”

Another full-line consideration came by way of the multipack dimensions themselves. Shrink bundled film tightly hugs the cylindrical seafood cans, making for a rounded corner shape in the multipacks. Cartons are cubes with pointed right angles at the corners. This difference was most noticeable at the downstream Standard Knapp tray packers.  Downstream of the Meridian XR MPS-300 (upper right middle), operators attend to the lane guardrails at the point of a 180-deg turn on the line after cartoned product is laned.

Downstream of the Meridian XR MPS-300 (upper right middle), operators attend to the lane guardrails at the point of a 180-deg turn on the line after cartoned product is laned.

“We had to put in a changepart kit with lifting lugs on it in the grouper pin area,” Carney says. “That’s because we run loose product and loose stacks on that line as well. The grouper pins wouldn’t work with the cartons because of the square corner, so in advance, Standard Knapp had built that changepart kit for us and did the conversion on the tray packers for us while we were setting up the cartoner.”

The tray packers also require a certain amount of backpressure to operate. A little spare backpressure wasn’t a problem in the previous format since the shrink film adheres tightly to the rounded corners of the rigid cans. But the corners of the paperboard cartons are filled with empty space since their can contents are cylindrical. That led to some corner crushing issues until the optimal backpressure could be sorted.

“We added some additional photo eyes to the system to give us some more finite control, and that solved the problem,” Costello says. “That was something where we had to find a sweet spot to maintain backpressure, but still keep the carton corner intact.”

Rockwell and Allen Bradley controls are used for all control logic on the equipment installation, including the infeed to control backpressure on the Meridian XR MPS-300, and the discharge to control backpressure on the Standard Knapp unit.

Yet another consideration ahead of the tray packers involved lane-width readjustments that were necessary on conveyors to account for both the square corners on the cartons and the new width—paperboard is thicker than shrink film, so it added a small but significant width to the multipacks.

“It took a couple of days to get all the catch points sorted out,” Carney adds. “The lane dividers were already there, we just had to move them, realign them, and make sure there were no joints or spots that a square corner would catch between two dividers.”

Finally, there were modifications necessary to the pallet patterns. The tray size had had to get slightly bigger to accept the wider cartons, changing the pallet pattern overhang quite a bit.

“Because this was a new item that Bumble Bee was introducing, we made the decision not to have any overhang,” Butler says. “We did a full-scale change of what our expectation was on the pallet configuration of the carton size. Bumble Bee made that change to make sure that overhang isn’t an issue. We’re working now with customers to see we if we can actually get more cases per pallet by adding an overhang back, since that’s what we’ve done before. We’re working with them to gradually get back to that overhang, at this point, to pack more cartons in.”

Ascending the learning curve

Like any complex line integration, the early days of the installation weren’t without their share of heartburn as operators ascended a steep learning curve. Butler planned for this honeymoon phase by building out plenty of extra product stock in the months leading up to the installation. He also built planned dips in production into the schedule, with lower case volume output planned during the installation. Plus, in a pinch, there was also a backup cartoner option onsite. It was simple and ran at very slow speeds, but it was available as the team learned the new Meridian XR MPS-300 machine, and essentially, a whole new packaging line format.

“Anytime that you’re taking a brand-new machine and integrating legacy upstream and downstream equipment, there are going to be challenges. Especially given that we’re doing a full format change and that we’re moving from shrink bundling to a cartoner, there was some extensive work that was done,” Costello says. “From all the conveyance to the tray packer modifications that needed to be done downstream, and palletizer changes as well, there was a lot of change. Then, like Joe [Carney] mentioned, one of the big challenges was being able to rotate the cartons and lane them and at speeds to 200 to 300 cartons per minute on some of the formats.”

Bumble Bee had been to no fewer than three FATs in Covington, Ky. for this machine. Over the course of those tests, R.A Jones had proven out the Meridian’s capability for comparable changeover times to the legacy shrink bundling system, plus an operating efficiency of 97% and saleable product efficiency of 99.75%. Since the FATs demonstrated that the machine could hit these marks, Carney had no problem being able to tell his operators that they were expected to do the same. Once the Meridian XR MPS-300 was up and running in Sante Fa Springs, figuring out the changeovers—even with Acc-U-Change—presented another learning curve. They’ve since gotten up to speed.  Cartoned product is oriented and laned after outfeed from the cartoner.

Cartoned product is oriented and laned after outfeed from the cartoner.

“One thing we’ve requested from R.A Jones was an estimated changeover time, and we made them prove that to us at one of the FATs, that we could actually change the machine over in the timeframe that they stated the machine could be changed over,” Carney says. “So we had a realistic expectation for the time it would take for our operators and mechanics to do the changeovers. Our people had to get used to the machine, of course, and they struggled with changeovers at first. The [times were] extended at the beginning, but right now, they’ve had enough experience on the line to the point where they’re hitting those estimated times.”

Changeover is now at the FAT-estimated time of between 20 and 30 minutes, depending on the differences between outgoing and incumbent pack format, and how many parts really need be changed. The time is about three to five minutes longer than changeovers on the legacy shrink bundling equipment, but given the complete substrate change, it’s hard to compare apples to apples.

“It took us a few weeks after the machine was installed to get ourselves to that point. There was some training and coordination between departments, especially between operations and maintenance,” Butler adds. “In changeovers, those two departments become a single entity. It took coordination and a team approach to get the formats to changeover more efficiently.”

As the teams settled into their processes, Costello says that’s when he could see the emergent advantages of the Acc-U-Change system, especially in its repeatability. Even though the physical act of changing over might take a little longer, the time previously needed for ramping up and dialing in is nearly eliminated in the vertical startup. Acc-U-Change quickly runs through 74 dry cycles, with no product or paperboard (so zero scrap), after a changeover to validate changeparts are correct and in working order. That guarantees a so called “0 to 60” startup on changeover.

“A lot of times, even after a changeover is completed, there are additional adjustments that need to be made, tweaks and things like that, to get a machine ready to run. That’s even after the physical parts have been switched out,” Costello says. “That’s where we’ve seen a big benefit. Whenever we actually complete the changeover, there’s very minimal additional adjustments that are needed to hit our target speeds.”

Bumble Bee’s full carton line today

The packaging line at the Santa Fe Springs begins with filled, seamed, brightstock cans of seafood being introduced to the packaging line via one of two different style baskets coming off of a lowerator. One is a round “jumble” basket, where product is “jumble loaded” off of the infeeding lowerator. This is primarily for the 5-oz generic products. The other is more of a square, busse-style basket in which cans are layered and separated by a divider sheet. The latter basket format tends to be used for 12-oz products and the 7-oz premium products.

Regardless of entry basket, all product then is introduced to a small mass accumulation table that acts as a buffer ahead of two parallel P.E. Labellers. Each places glue-applied labels on the brightstock at 1,000 cans/min.  Infeed of 5-oz and 7-oz canned and glue-applied labeled product into the cartoner at the Santa Fe, Calif. Bumble Bee facility. Note the layout of three parallel tracks, with product first entering the space and feeding the cartoner on the center track. After product is cartoned and laned, it turns sharply 180 deg, carrying product downstream while parallel to the cartoner. Product then takes another, wider 180-deg turn around the cartoner, and finally travels parallel to the previous two tracks again for tray packing.

Infeed of 5-oz and 7-oz canned and glue-applied labeled product into the cartoner at the Santa Fe, Calif. Bumble Bee facility. Note the layout of three parallel tracks, with product first entering the space and feeding the cartoner on the center track. After product is cartoned and laned, it turns sharply 180 deg, carrying product downstream while parallel to the cartoner. Product then takes another, wider 180-deg turn around the cartoner, and finally travels parallel to the previous two tracks again for tray packing.

X-ray detection via Peco InspX equipment is next, with no need for coding and marking since the cans are coded prior to, or at the point of, retort. Another small amount (10 to 12 ft) of accumulation occurs ahead of a can stacker by Arrowhead. The stacker is capable of stacking 5-oz cans up to six-high, or 7-oz cans up to four-high. Those discharge into another accumulation station, after which product can either enter the Meridian XR MPS-300 cartoner, or be diverted past the cartoner to the tray packers in the case of running loose cans, tray-packed with overwrap.

Having been cartoned in the R.A Jones machine, then turned and laned on the Nercon and Intralox equipment respectively, product turns 180 deg and is conveyed parallel to the infeed, then turned again downstream to the Standard Knapp tray packer. Depending on the customer requirement, it may then undergo plastic overwrap. Carney says the cartons fit snuggly into the trays, but some retail customers still want the extra insurance of plastic overwrap. The overwrapper and heat tunnel are modular sections of the Standard Knapp tray packers, so they can be engaged when needed, or more commonly left unused as product runs through without overwrap or heat being applied.

“We’re working with our customers to see if we can do away with the plastic overwrap,” Butler says. “It adds extra plastic unnecessarily (even though the stretch wrap is able to be recycled by the retailers prior to putting on shelves), and it’s more equipment that could cause extra downtime on the line.”

A QA inspection of the packed tray, with or without overwrap, occurs thereafter, and passing trays are then inclined up overhead to a Matthews palletizer. Corner boards are placed around the cartons during palletization, preventing the slick paperboard finish from sliding on the pallet during the pallet-wrap process. Stretch wrapping occurs on an Orion Packaging Systems stretch wrapper, and finally, pallets are discharged to await shipping.

| Read a column about how this article came together over nearly two years, and about how a CAPEX project like this one inspired employee engagement and excitement |

For Butler, the success of the project only moves the continuous improvement ball down the field, and highlights another bottleneck to tackle next. But that’s a good thing. “We’re Bumble Bee, and this facility is our hive of tuna operations,” Miguel Diaz, the forklift driver on that packaging line who came up with the Queen Bee moniker, said at the machine dedication, over cake. “This is our Queen Bee.”

“We’re Bumble Bee, and this facility is our hive of tuna operations,” Miguel Diaz, the forklift driver on that packaging line who came up with the Queen Bee moniker, said at the machine dedication, over cake. “This is our Queen Bee.”

“On the smaller packs, the four-packs, the equipment isn’t only meeting our speed goals. It looks like there’s potential for it to surpass them and go even faster. Since it’s not the bottleneck anymore, it’s making us look at other facets of the line to see if we can get that speed increased. Now the worry isn’t multipacking operations, the worry is what can we do on the rest of our equipment to make sure we’re getting the most speed that we can. It’s a good problem to have.” PW