From a big-picture perspective, the growing demand for PCR is a good thing both economically and environmentally, according to Andrew Brown, head of Plastics and Recycling at market intelligence consultancy Wood Mackenzie. The use of recycled plastic in packaging, particularly rPET, is an instrument that can help brands and CPGs decarbonize and lower their greenhouse gas footprint.

But the problem packagers face is that the brands and CPGs don’t constitute the only vertical market seeking to employ PCR to help decarbonize. Automobile manufacturers, pipe and drainage manufacturers, and textiles industries are getting in line to take advantage of PCR’s carbon footprint-reducing properties.

“Everyone wants recycled material. For a bunch of folks at a plastic recycling conference. that's a great news. It's a good problem to have,” Brown says. “The challenge is figuring out what's driving this demand. Is it a drive for more responsible waste treatment, or is it for reduced carbon intensities? I think it's both. And as the industry evolves, not just the plastic value chain is looking for options to decarbonize. Every industry that consumes plastic is looking for options to reduce their carbon footprint. One of the most prominent solutions for those industries that are highly plastics-dependent is to look at recycled materials as an option to reduce their carbon footprint. And it turns out that the two biggest contenders here are packaging and apparel.”

Packaging vs. apparel: Face to face comparison

Packaging currently commands 27 million tons of PET resin overall, substantially less than apparel’s 36 million tons. Demand for rPET among packagers and CPGs is largely concentrated in Western countries in North America and Europe, while the apparel rPET demand comes mostly from East Asia, where the PET fiber industry is concentrated. Packaging generally has higher quality material standards than do rPET fabrics—that’s especially true of food-grade rPET.

“There are differences there between staple fiber and filament fiber, but in either case, textile-bound rPET fibers aren’t subject to nearly the [level of] certifications that packaging rPET has to undergo,” Brown shares.

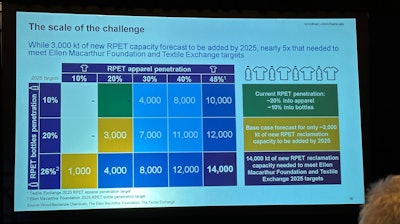

Comparatively low quality rPET—too low for many packaging applications—remains well-suited (forgive the pun) for apparel because it can be dyed to any color. Another foundational difference between the packaging and apparel markets is that the use of rPET in apparel is a traditional, entrenched practice, whereas rPET use for packaging is a newer, emerging end-use for recyclate. As far as PCR usage goals broadcasted by the two industries, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation says that its signatories’ packaging should have at least 26% recycled content by 2025. The Textile Exchange is aiming for 45% recycled content among its signatories by 2025.

“So massive goals for use of PCR, mostly rPET, are being set by these associations,” Brown says. “And the question then becomes, what that means for demand? Do we have enough of it? What kinds of new supply is going to be needed for rPET material if these targets are to be met?”

Currently, we're looking at approximately 10% penetration of rPET into the packaging sector. On the apparel side, that number is about 20%.

“So if these goals are to double, or more than double over the next two to three years (as the targets have been set for 2025), that means we’re looking at nearly 14 million tons of new rPET supply that are going to be necessary to meet expected demand over the next two to three years. That's a massive number.”  This chart reveals the current penetration of rPET, the forecast amount, and the nearly 5 times the forecast amount that's needed to fill promised NGO targets

This chart reveals the current penetration of rPET, the forecast amount, and the nearly 5 times the forecast amount that's needed to fill promised NGO targets

It should be noted that not every company among either the packaging sector or apparel sector are signatories to their respective sustainability NGOs—Ellen MacArthur Foundation and Textile Exchange. But the big brands are. For instance, Coca-Cola is a signatory to Ellen MacArthur, and Adidas is a signatory to the Textile Exchange.

“The big brands are clearly aligned with the objective to secure recycled material feedstocks,” Brown says. “With 14 million tons of new demand is coming online over the course of the next two years, the question immediately becomes, where does that come from?”

Brown sees three domestic routes to increased rPET supply that, taken together, may be able to satisfy demand, at least here in the U.S.

Legislation can help, but it's fractured

The first and most obvious option is to simply raise collection rates, but that’s not so simple. States like California, Colorado, Oregon, and Maine have implemented EPR laws and bottle deposit schemes that have improved collection, but the United States remains far from united in its approach. As big as California is, four states out of 50 doesn’t move the needle as much as the industry would like.

“That's not going to completely change the collection rate—we expect that those states’ actions will raise it by something like 5% here in the U.S., from 25% to 30% over the course of the next three years,” Brown says. “Collection is headed higher, but not by nearly enough. So, what are the other options available in the industry?”

Brands and sorters tag team for improved sortation

Brown looks to new innovations to help make up the rPET deficit, and advanced sorting is the result of a host of new technologies working together. On the brand or CPG side, practices like digital watermarking show promise to aid in downstream collection. Companies in Europe like Digimarc are pursuing and now piloting options for on-pack chemical tracers and on-pack digital watermarking, easily readable on-pack signifiers that broadcast to a MRF that a given package or container is high-quality, recoverable PET. A corollary on the back-end—at the MRFs who are receiving these materials from brands, via consumers—are new technologies like advanced robotics, computer vision, AI, and near-infrared sorting. Brown listed several new, startup-type ventures that are pursuing these advanced sorting systems. So both the CPGs and the MRFs have parts to play in advanced sorting and recovery.

“Advanced sorting improves yields and improves bale quality,” Brown says. “We expect that yields will improve over the course of the next three years, as many of these systems are implemented. We think that yields could increase by something like 5%, from the current rate of 65% to 70%, up to 70% to 75%, unlocking more supply of rPET. But more is still needed.”

Advanced recycling a slow-moving magic bullet

Wood Mackenzie expects high growth rates in chemical recycling over the next 10 to 20 years, with a compounded annual growth rate approaching 15% through 2040. Packaging World editors can verify that there has been a massive influx of new chemical recycling facility openings in the past year alone.

“That's from a small base,” he clarifies. “However, we expect that that's going to be about 10% of the total packaging waste recycling in 2040, which is essentially what we mechanical recycling is across packaging now. We expect chemical recycling to play a significant part, not by 2025, but over the course of the next 10 or 20 years and unlocking supply to meet these targets that we've set.”

Are all of these tools and technologies enough to meet demand for rPET? At this point, the answer is no, according to Brown. More is still needed.

Imports augment rPET supply, but defeat the purpose

“We expect that imports of rPET flake are likely headed higher over the course of the next two to five years,” Brown says. “Which begs the question, where does it come from? Is it from Latin America? Africa? Could we look as far as Asia, especially with food-grade rPET certification becoming more prominent in Asia? Maybe, but I think a lot of it, at least in the near term will come from Latin America.”

But a key side effect to importing rPET brings the entire conversation full circle. To import rPET, flake even from relatively nearby Latin America, only adds significant carbon footprint to the whole endeavor. And remember, reducing carbon footprint is the ultimate goal of sourcing and using rPET anyway, whether in packaging or in apparel.

“As we think about the carbon footprint associated with importing material, there's a significant advantage if we secure the supply domestically, rather than importing it,” Brown concludes. “You add up to up to 40% more emissions if you import bail or import flake, rather than sourcing it domestically.”

This material is still more competitive than its virgin alternative, but according to Brown and Wood McKenszie, the best path is to continue to look for options domestically to secure materials both reduce carbon intensities, and also reduce plastic waste footprint. PW