In 1795, a farmer and grain mill operator named Jacob Beam produced the first barrel of whiskey that would become Jim Beam, the world’s top-selling bourbon. On the other side of the world a century later, Shinjiro Torii founded Suntory in Japan in 1899, the first whiskey to suit Japanese palates. But it wasn’t until 2014 that, by combining the world leader in bourbon and the pioneer in Japanese whiskey, Beam Suntory of Chicago was born as a subsidiary of Suntory Holdings Limited of Japan.

In a whiskey and bourbon industry characterized by resistance to change, a focus on heritage, and an adherence to the original ways of distilling, packaging operations at Beam Suntory are anything but antiquated. To the contrary, Packaging World recently heard about a unique and forward-looking revolution in changeparts maintenance and changeover management on packaging equipment at the Beam Suntory Frankfort, Ky., facility. The project demonstrates how the company strikes a balance between a heritage product on the distilling side and continuous improvement and lean manufacturing on the bottling and packaging operations side.

A lot of SKUs, a lot more changeparts

With nine lines that are each bottling a wide breadth of different spirits products—bourbon, tequila, vodka, etc.—and each in a multitude of unique bottle, closure, and label formats, the Frankfort bottling plant has a lot of SKUs to manage. Naturally, these lines require a preponderance of changeparts, organized into sets, to accommodate each possible process on each line.  Bottling operations at Beam Suntory span nine separate filling, capping, and case packing lines that share similar and often overlapping, but not identical, inventories of change parts like guard rails, starwheels, and timing screws.

Bottling operations at Beam Suntory span nine separate filling, capping, and case packing lines that share similar and often overlapping, but not identical, inventories of change parts like guard rails, starwheels, and timing screws.

The Beam Suntory facility has sets for changeovers at each of the five major pieces of equipment on each line—sets at the rinser, sets at the filler, sets for capping operations, sets for labeling, and sets for case packing. Spanning more than nine bottling lines and varied equipment from the likes of KHS, Standard Knapp, Zalkin, and Douglas Machine, this quickly adds up.

“We have around 50 physical molds that combine to run over 80 different sets, with between 25 and 40 changeparts in any one set,” says Matt Roberge, Training Program Manager, Beam Suntory. “They run over 80 different sets because some of them are combined for specific bottles with specific labels. So, you could say there’s more than 60 physical sets, but they make up roughly more than 80 sets, on several lines, and we do more than 500 SKUs. Realistically, we are storing way over 2,000 changeparts.”

Efficient changeover is key for productivity and uptime. For Beam Suntory, that had previously meant parts carts and other storage solutions for changeparts right on the line, physically located next to the equipment or in consolidated areas that required it at point-of-use. The team was storing parts wherever they had space with parts organized on shelves and racks.

The process was completely decentralized, with each line having its own dedicated suite of changeparts and disparate sets of dedicated operators with their own clusters of knowledge about how to keep machines running best and uptime optimized.

“A lot of times operators would find that a certain worm [timing screw] works better with one set than the set it actually belongs to, and they’d take that worm, and they’d make it part of their own personal operational knowledge,” Roberge says. “But operators on the next line over might not know that.”

There are inherent redundancies in this approach. For instance, certain starwheel or timing screw sizes or configurations on Frankfort’s filler on one line might be the same as those on others. And they might be running on different days. Extrapolate those potential redundancies across the entire facility, and the potential for extraneous inventory gets bigger, with each line having entirely dedicated changeparts.

Meanwhile, in a facility where space was already at a premium, operators’ walkways around each individual line were choked with changepart storage carts. According to Roberge, the company had been aware of the potential for improved efficiency in the way the company addressed changeparts, they just didn’t have the time or space to act on it.

It wasn’t until Beam Suntory partnered with Change Parts, Inc., a Ludington, Mich., member of the AMET Packaging family, which includes such OEMs as E-Pak and Oden Machinery, that Beam Suntory unlocked the lean processes that would transform its changeparts approach.

STR project kicks off

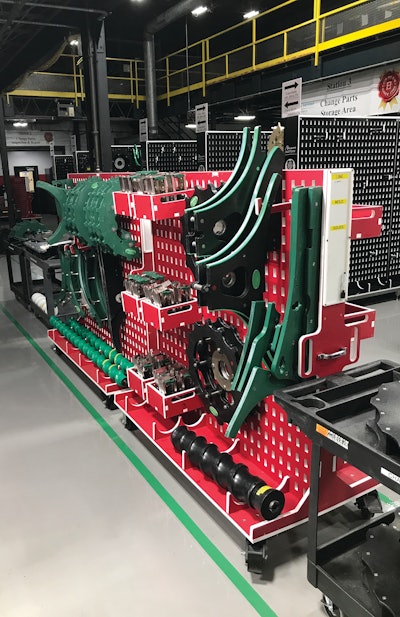

Roberge, who was project manager on the changeparts centralization project, and the Change Parts Inc. team set out to improve changeover efficiency at Beam Suntory in what can be considered a Setup Time Reduction (STR) project. Setup Time Reduction enables the team to reduce the changeover time, thus compressing the time between runs but increasing availability of lines. To accomplish this, it requires that as much of the changeover work as possible is done while the equipment is still running the previous parts on the previous SKU, before the actual changeover to the next SKU happens.  The new, dedicated space for change parts management includes inventory, cleaning, storage, and maintenance of changeparts for the entire Frankfort Beam Suntory facility. Lanes for inbound and outbound change parts carts keep workflow organized.

The new, dedicated space for change parts management includes inventory, cleaning, storage, and maintenance of changeparts for the entire Frankfort Beam Suntory facility. Lanes for inbound and outbound change parts carts keep workflow organized.

Parallels from other industries include the culinary practice of mise en place, a process by which the ingredients are sliced, spices are measured, and pots and bowls chosen and arranged before a chef ever begins cooking. An analogy that applies more broadly is laying out your more formal business attire the night before a big meeting, thereby taking the decision-making, time, and thinking out of getting dressed before a high-stress presentation.

To incorporate the STR methodology, the Frankfort team identified a single room where they could centralize all of the changeparts across Beam Suntory’s nine lines, organized into rollable cart sets and molds. They then identified a single, cross-functional team to manage, clean, repair, and if necessary, reorder the changeparts out of the central changeparts room. This was a big step away from the highly specialized but disparate operator teams that were intimately close to their own lines and processes, but much less so on other lines.

We can imagine the process that was implemented here as an ongoing cycle of parts moving in and out of the central location. It’s easiest to begin to follow the cycle as the changeparts carts are coming back into the room after they’ve been removed from a machine and changed out for a different set. A set comes into the changeparts room, where the changeparts specialist first inspect them for damage. In any bottling plant, there’s a lot of glass involved. Shattered glass can easily be embedded in those parts. If nobody was looking out for embedded glass in the changeparts, and they were installed and run for an entire shift, that could spell trouble.

“That’d be hundreds of bottles they’d have to rework or destroy because they cut a label or scored a bottle,” Tony Swedersky, President of Change Parts, Inc. says. “After inspection, these parts go through an industrial washer. In the beverage industry, a lot of these parts get sticky, and a lot of other manufacturers’ [changeparts storage systems that are dedicated to specific] lines don’t allow for those parts to get routinely washed. They’re always on the line, so there’s not much chance for them to leave the line to go get cleaned.”  Changeparts storage and maintenance prior to the changeparts and changeover efficiency project with Change Parts Inc.

Changeparts storage and maintenance prior to the changeparts and changeover efficiency project with Change Parts Inc.

Under the previous system, operators were dedicated both to their machines’ operation and the many changeparts needed to keep the machines going. With the new system, a changeparts team is dedicated only to the changeparts. This brings the changeparts under a higher degree of scrutiny, and potential problems like embedded glass and damaged parts are more likely to be caught. This is both a scrap issue for bottles, labels, and corrugated cases and a safety issue for operators.

“Through the new inspection process in the changeparts room, dedicated parts operators are looking for broken or mangled or damaged parts that typical operators, who have bottling lines to be running, may not catch,” Swedersky says. “As they go through this process, the changeparts operators see it, they can order the part, repair the part, whatever is required to get it ready to go back on the shelf.”

Along with an industrial washer, the Frankfort facility’s new changeparts room also features a changeparts repair area, so the changeparts specialist can make repairs in the room versus moving parts to the shop at the other end of the site.  Labeled starwheels and other changeparts on a filler at Beam Suntory’s Frankfort location.

Labeled starwheels and other changeparts on a filler at Beam Suntory’s Frankfort location.

“There’s a person who’s back in the changeparts room looking at the bottling schedule every day to verify what sets will be needed for which lines,” Roberge says. “And though things sometimes change, they generally know what they’re running for the whole week, and they know when the changeovers are. So, if they know when a changeover is, then they can prep the carts with the correct changeparts—it could be 24 to 72 hours out, it just depends on the needs of the day. But even if that person running the changeparts room is not going to be in the following day, they can still prep the parts and arrange for the carts to get pushed out to the line.”

The centralized changeparts system still uses lean and just-in-time (JIT) principles, and the parts needed for any changeover are still available at the time of the changeover, just as they previously were. The difference is they’re prepped and ready more thoroughly than they ever were before, thus facilitating faster, more successful changeovers.

“What that saves the operators is the rework of any broken parts, and also parts cleaning,” Swedersky says. “Damaged parts are a big problem in bottling lines, and finding it early and fixing it before a changeover, not during, is a huge savings. More generally, operators know where the parts are, and the repairing, cleaning, and the downtime they’ve saved from having parts that are in good working order, have been the biggest savings in this project. And everything is still centrally located. It’s visually identified via their tagging system. So, all the lean principles are still there. It’s just, everybody thinks that lean only means parts being stored at point-of-use, not just ready at point-of-use. In practice, that was where a lot of the bad habits were happening, but not being seen or corrected.”

Results of centralization project

Roberge says his results have been “great,” though he’s still finding ways to continuously improve them. Anecdotally, it’s a difference between chaos and order in his mind. By eliminating cabinets and old carts from the floor, Change Parts’ regional sales manager Steve Leedham and Roberge were able to reclaim 1,200 sq ft of storage space on the bottling line—the size of a tennis court. This reclaimed space has been repurposed into functional spaces, like an easily accessible oil and lubrication area for which there previously wasn’t room.  Beam Suntory’s Matt Roberge opted for portable racks with an inverted ‘T’ shape to help save space both on the floor and in inventory in the dedicated changeparts department.

Beam Suntory’s Matt Roberge opted for portable racks with an inverted ‘T’ shape to help save space both on the floor and in inventory in the dedicated changeparts department.

With no closed, stationary cabinets, supervisors have much better visual management of their lines and people. It makes it easier for operators, too.

“Before, there were parts on the line, but some lines had parts near the end of the line that were stored under the depalletizer at the front of the line,” says Roberge. “I paced that out, and round trip, it was 400 feet that an operator had to walk, dig through parts, find the right cart, and then walk the whole thing all the way back to the front of the line.

“There was also a lot of downtime. For instance, a filler profile would miss a changeover, and the delay was due to missing changeparts. We’ve taken that away, and now when they need their parts, they’re clean, functional, and already there for the changeover.”

Beyond simply improving the lives of operators during changeovers, the regular, standardized maintenance and organization of changeparts has eliminated a range of issues. What follows were examples of typical issues experienced on the nine Frankfort packaging lines prior to the STR changepart reorganization:

• Changeover delayed due to missing changeparts; pins for stars locked in a toolbox

• Worn basket in case packer causing extensive breakage in same pocket

• Broken discharge star causing chipping to bottles

• Combined molds to form one set, caused tamper-evident band issues

• Improper back guide installed; parts not clearly marked

All of this caused overtime among operators, case holds, delayed production, and even cases destroyed. These situations have all but been eliminated by this project.

All of this comes with a cost, Roberge adds, but those costs are easily made up over the long term by eliminating scrap, improving ergonomics, and reducing setup time.  Cleaned, organized changepart racks in storage, prior to being deployed to their designated packaging line and filling application.

Cleaned, organized changepart racks in storage, prior to being deployed to their designated packaging line and filling application.

“At first, people are resistant to change, but this project has really turned into a success. We’ve had great feedback from our operators,” Roberge concludes. “The pictures don’t do it justice, though. We’ve improved our organization. It’s difficult to quantify the benefits, but they’re obvious and undeniable as we engineer mistakes out of the process.” PW