Packaging World editors got a lesson both in physics and cartoner history at the Triangle booth at PACK EXPO Las Vegas. Historically, low density polyethylene (LDPE) bags used in dry bag-in-box operations—with bagged product being automatically loaded into paperboard cartons—present a difficult prospect for horizontally oriented end-load cartoners. Such product has often remained the realm of top-load cartoners since the ‘pushing’ action most end-load cartoners employ is problematic. Putting standard laminated films into cartons, for small loose product like cereals or crackers, is one thing, since the bags are designed to be more forgiving. But another matter altogether is doing so with LDPE film bags, that are now preferred for their mono-material structure. This is especially for such bags holding larger loose product like frozen appetizers or frozen waffles. Horizontal pushing across a static plane creates the problems.

For instance, “frozen waffles have traditionally been a difficult for a typical end-load cartoners. That’s because you have maybe two stacks of five frozen waffles, and when you push them into a carton, they tend to shingle. And once they shingle and overlap, they’re very hard to get into the carton,” says John Cooke, director of sales, Triangle. “Because our Flex Cartoner uses technology that ‘shoots’ the bagged product into the carton instead of just pushing it in, it’s a gentler loading and we don’t have problems with shingling and bags getting stuck in the openings of erected cartons.”

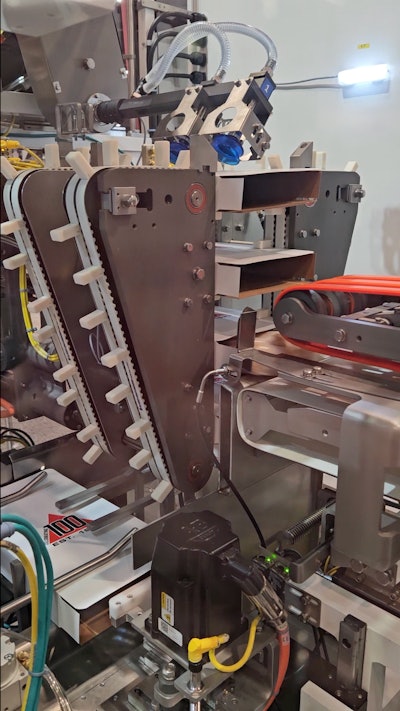

Here's what Cooke means by “shooting” the bags. Instead of being pushed off the conveyor into the carton by a pusher, LDPE bags with frozen waffles are conveyed at speed into the carton. Overhead belts (orange in the photo) can be added as a safety, in case there is a bulge or clump in the bag to try and settle it prior to being inserted into the carton. But when the cartoner is set up properly, the overhead belts never touch the top of the bag, the conveyor does the work of "shooting" the bag into the waiting carton.

Meanwhile, the cartons themselves aren’t resting on a plane. Instead, they’re being held in place by eight lugs (one at each corner on both open sides of the carton – see figure B). When the cartons are erected and oriented for filling with bags, they are squeezed a bit to bow the top and bottom of the carton, giving the bags a larger target to hit as they’re shot from the conveyor across the air gap into the carton mouth.

“But on traditional end-loads, you’re compressing, nearly crushing the bag to make sure it gets into the carton,” Cooke added. “We’re really excited about this.”

All in all, the Triangle dry product bag-in-box Flex Cartoners are a compact solution that the company says automates the production process while providing greater flexibility, lower maintenance, and reduced downtime. Automatic carton filling machines easily load one or more bags into the same box with single, twin-, and triple-pack bag-in-box capability, in both for laminated multi-layer films and mono-material LDPE. This makes these cartoners a strong alternative to top-load carton loading, the company says.

Other features of these machines include various levels of sanitation to meet any product’s requirements, including painted or stainless steel washdown frames. Cooke mentioned that the Flex Catoners for bag-in-box are a viable option for various products, including cereal, powders, baking mix, and grain applications, as well as for contract packagers and other companies running multiple carton sizes. Changeover is quick and simple, he added, with changeover to full production in less than 15 minutes.

Triangle’s bag-in-box cartoners are designed to be paired with current generation high-speed continuous motion vf/f/s machines, such as the Triangle X-Series. Offering loading and indexing speeds up to 100 cartons per minute, this perfectly matches the vf/f/s output for most bag-in-box applications.